C/C++ Programming Tips

- 1.

char**&const char** - 2. structure parameter passing

- 3. declaration & definition

- 4. arrays

!=pointers - 5. interpositioning

- 6. a few things about the stack

- 7. array parameters & pointer parameters

- 8. array and pointer parameters changed by the compiler

- 9.

sizeof( long ) == 8? - 10.

charvs.wchar_t - 11.

newthrowing an exception, not returningnullptr - 12.

newvs.malloc() - 13. setting

nullptrafter freeing - 14. memory allocation

- 15.

reinterpret_castis portable - 16. memory layout of C++ classes

- 17. signed division

- 18.

auto&&auto* - 19. literal pooling

- 20.

std::string_view - 21. initialization order

- 22. lvalue vs. rvalue

- 23. RVO (Return Value Optimization)

- 24. one function embracing lvalue and rvalue arguments

- 25. derived copy constructors

- 26.

flush() - 27. text mode vs. binary mode

- 28. errors in constructors

- 29. conversions for boolean expressions

- 30.

std::vector<bool> - 31.

std::span - 32.

try_emplace()onstd::map - 33. capturing lambda

- 34.

std::erase_if() - 35.

std::random_device - 36. thread local storage

- 37. spurious wakeup

- 38.

std::async() - 39. link time optimization

- 40. name mangling

- 41.

extern "C" - References

1. char** & const char**

char* cp;

const char* ccp;

ccp = cp; // this is legal

char** cpp;

const char** ccpp;

ccpp = cpp; // compile error!

In the case of char* and const char*, they are the pointers to char and const char. So, they are for the compatible types of char, and just differ in whether they have the const qualifier.

In the case of char** and const char**, however, they are the pointers to char* and const char*, more specifically (char) * and (const char) *. So, the types of these pointers are different since their original types are a pointer of char and a pointer of const char.

On the other hand, the following code is valid. Note that const char** and char* const* are clearly different.

char** cpp;

char* const* cpcp;

cpcp = cpp;

2. structure parameter passing

Parameters are passed in registers for speed where possible. Be aware that an int i may well be passed in a completely different manner to a struct s whose only member is an int. While assuming an int parameter is typically passed in a register, structs may be instead passed on the stack.

3. declaration & definition

Variables must have exactly one definition, and they may have multiple external declarations. A declaration is like a customs declaration. It is not the thing itself, merely a description of some baggage having around somewhere. But, a definition is the special kind of declaration that fixes the storage for a variable.

- definition: occurs in only one place. specifies the type of a variable. reserve storage for it. e.g.

int arr[100]; - declaration: can occur multiple times. describes the type of a variable. is used to refer to variables defined elsewhere. e.g.

extern int arr[]

The declaration of an external variable tells the compiler the type and name of it, and that memory allocation is done somewhere else. For a multiple-dimensional array, however, the size of all array dimensions except the leftmost one has to be provided.

4. arrays != pointers

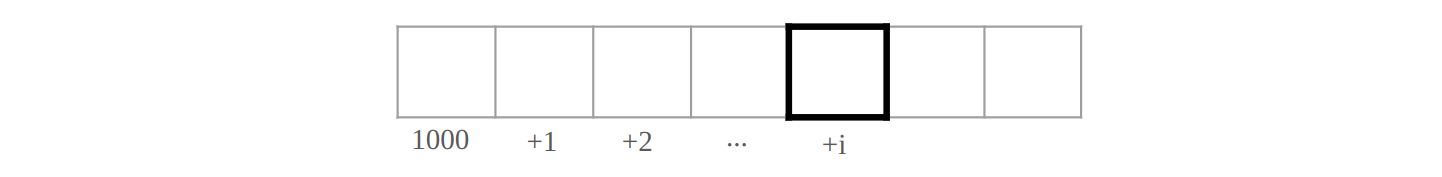

In the case of accessing a[i] after char a[9] = "abcdefgh";, the compiler symbol table has a as address 1000 at compile-time, for example, as below. Then, a[i] can get the contents from address (1000 + i) after getting value i and adding it to 1000 at run-time.

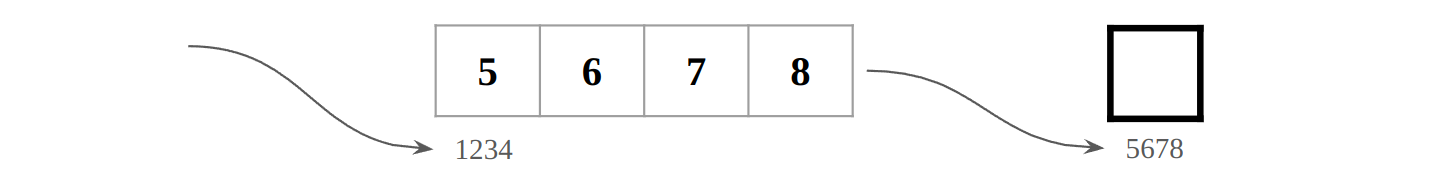

This is why extern char a[] is equal to extern char a[100]. The compiler does not need to know how long the array is in total, as it merely generates address offsets from the start. In contrast, extern char* p tells the compiler that p is a pointer and the variable pointed to is a character. To get the character, the compiler symbol table has p as address 1234 at compile-time, for example, as below. Then, *p can get the contents from address 5678 after getting it from address 1234 at run-time.

Differences between arrays and pointers can be summed up as follows.

| arrays | pointers |

|---|---|

| holds data | holds the address of data |

data is accessed directly, so a[i] is the contents of the location i units past a | data is accessed indirectly, so *p is the contents after getting the contents of p first. If the pointer has a subscript [i], the contents should be the one of the location i units past p. |

| commonly used for fixed number of elements of the same type of data | commonly used for dynamic data structures |

| implicitly allocated and deallocated | commonly used with malloc() and free() |

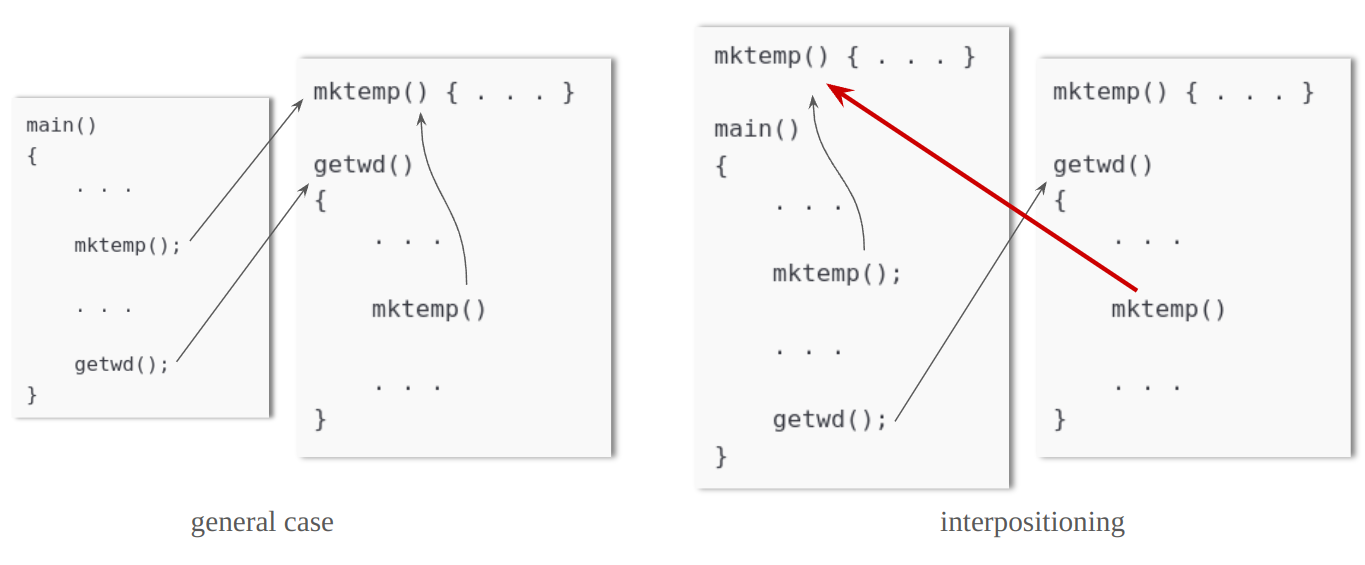

5. interpositioning

Interpositioning or interposing is the practice of replacing a library function with a user-written function of the same name, which is very dangerous. With interpositioning, it replaces the system calls as well as user code.

6. a few things about the stack

- A stack frame might not be on the stack. Although it is said that a stack frame is pushed on the stack, an activation record need not be on the stack. It is actually faster and better to keep as much as possible of the activation record in registers.

- On UNIX, the stack grows automatically as a process needs more space. The programmer can just assume that the stack is indefinitely large. Although the kernel normally handles a reference to an invalid address by sending a segmentation fault to the process, a reference to the red zone region, which is located just below the top of the stack is not considered as a fault. Instead, the operating system increases the stack segment size by a good chunk.

- The method of specifying stack size varies with the compiler. Compiler vendors have different methods for doing this.

7. array parameters & pointer parameters

char ga[] = "abcdefghijklm";

void passArray(char ca[10])

{

printf( " address of array parameter = %#x \n", &ca );

printf( " address (ca[0]) = %#x \n", &(ca[0]) );

printf( " address (ca[1]) = %#x \n", &(ca[1]) );

printf( " ++ca = %#x \n\n", ++ca );

}

void passPointer(char* pa)

{

printf( " address of pointer parameter = %#x \n", &pa );

printf( " address (pa[0]) = %#x \n", &(pa[0]) );

printf( " address (pa[1]) = %#x \n", &(pa[1]) );

printf( " ++pa = %#x \n", ++pa );

}

void main()

{

printf( " address of global array = %#x \n", &ga );

printf( " address (ga[0]) = %#x \n", &(ga[0]) );

printf( " address (ga[1]) = %#x \n\n", &(ga[1]) );

passArray( ga );

passPointer( ga );

}

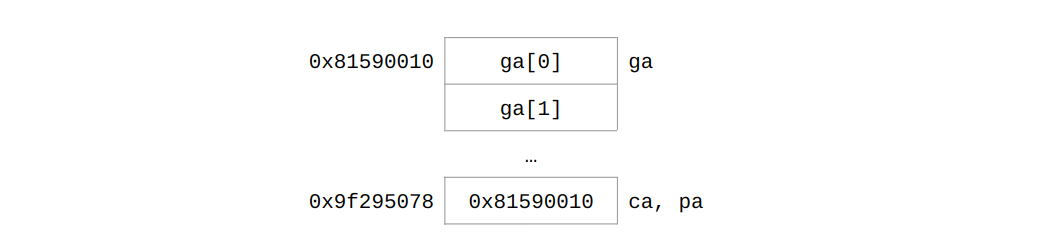

The output of the above code could be as follows.

address of global array = 0x81590010

address (ga[0]) = 0x81590010

address (ga[1]) = 0x81590011

address of array parameter = 0x9f295078

address (ca[0]) = 0x81590010

address (ca[1]) = 0x81590011

++ca = 0x81590011

address of pointer parameter = 0x9f295078

address (pa[0]) = 0x81590010

address (pa[1]) = 0x81590011

++pa = 0x81590011

- The results of

ga,ca, andpaare the same. Only the results of&caand&paare different. garepresents the address of the first element of the arrayga.&garepresents the address of the arrayga.gaand&gaare the same. Butga + 1points to the second element of the arrayga, and&ga + 1points to the next one by the size of the arrayga, which means undefined behavior.- The addresses of

gaandga[0]are the same sincegais the original. - When calling the functions, the address of

gais copied and passed to them, which means that the addresses ofcaandpaare not the same as the address ofga.

8. array and pointer parameters changed by the compiler

The “array name is rewritten as a pointer argument” rule is not recursive. An array of array is rewritten as a “pointer to array” not as a “pointer to pointer”.

| argument | matched parameter |

|---|---|

array of array such as char c[8][10]; | pointer to array such as char (*c)[10]; |

array of pointer such as char *c[15]; | pointer to pointer such as char** c; |

pointer to array such as char (*c)[64]; | does not change |

pointer to pointer char** c | does not change |

Note that char *c[15] is a vector of 15 pointers-to-char and char (*c)[64] is the pointer to array-of-64-chars. The reason char** argv appears is that argv is an array of pointers, which is char *argv[]. This decays into a pointer to the element, namely a pointer to a pointer.

9. sizeof( long ) == 8?

In general, the size of long type is 4-byte in the 32-bit system or 8-byte in the 64-bit system. However, this size varies by platform and not fixed to 4-byte. Fortunately, other types are fixed bytes except for long type.

| 32-bit Windows/Linux/Mac | 64-bit Windows | 64-bit Linux/Mac |

|---|---|---|

| pointer size is 4 | pointer size is 8 | pointer size is 8 |

| sizeof( char ) is 1 | sizeof( char ) is 1 | sizeof( char ) is 1 |

| sizeof( short ) is 2 | sizeof( short ) is 2 | sizeof( short ) is 2 |

| sizeof( int ) is 4 | sizeof( int ) is 4 | sizeof( int ) is 4 |

| sizeof( long ) is 4 | sizeof( long ) is 4 | sizeof( long ) is 8 |

| sizeof( long long ) is 8 | sizeof( long long ) is 8 | sizeof( long long ) is 8 |

| sizeof( float ) is 4 | sizeof( float ) is 4 | sizeof( float ) is 4 |

| sizeof( double ) is 8 | sizeof( double ) is 8 | sizeof( double ) is 8 |

Although it is speculation, this inconsistency seems because of the DWORD type in Windows, which is declared as typedef unsigned long DWORD. DWORD is a variable used assuming 4 bytes, so if this size would be changed to 8-byte, DWORD size should be also changed, which means a disaster of worldwide code.

10. char vs. wchar_t

The basic idea behind Unicode is to assign every character or glyph from every language in common use around the globe to a unique hexadecimal code known as a code point. When storing a string of characters in memory, a particular encoding is selected among the following. Note that UTF-16 and UTF-32 encodings can be little-endian or big-endian.

- UTF-32: Each Unicode code point is encoded into a 32-bit value, which is the simplest Unicode encoding.

- UTF-8: Each Unicode code point is encoded into a 8-bit value, but some code points occupy more than one byte. This is known as a variable-length encoding, or a multibyte character set(MBCS) because each character in a string may take one or more bytes of storage. The first 127 Unicode code points correspond numerically to the old ANSI character codes.

- UTF-16: Each character in a UTF-16 string is represented by either one or two 16-bit values. This is known as a wide character set(WCS).

The char type is intended for use with legacy ANSI strings and with MBCS including UTF-8. The wchar_t type is a wide character type, which is intended to be capable of representing any valid code point in a single integer. The C++ standard does not define the size for wchar_t. So, its size is compiler- and system-specific. It could be 16-bit for UTF-16 or 32-bit for UTF-32. Under Windows, however, the wchar_t type is used exclusively for UTF-16 and the char type is used for ANSI strings and legacy Windows code page string encodings. When reading the Windows API documents, the term ‘Unicode’ is always synonymous with WCS and UTF-16 encoding. This is a bit confusing because Unicode strings can in general be encoded in the non-wide multibyte UTF-8 format.

Since C++20, char8_t, char16_t, or char32_t stores at least each 8, 16, or 32 bits. This type can be used as the basic building block for UTF encoded Unicode characters. The benefits of using these types instead of wchar_t is that the standard guarantees minimum sizes for these types, independent of the compiler. There is no minimum size guaranteed for wchar_t.

11. new throwing an exception, not returning nullptr

new expression throws an exception to report failure to allocate storage, and does not return nullptr. However, new accepts an argument because it works like a function. new(std::nothrow) can be used for returning nullptr when bad allocation happens.

#include <iostream>

#include <new>

int main()

{

try {

while (true) new int[100000000ul];

}

catch (const std::bad_alloc& e) {

std::cout << e.what() << '\n';

}

while (true) {

int* p = new(std::nothrow) int[100000000ul];

if (p == nullptr) {

std::cout << "Allocation returned nullptr\n";

break;

}

}

return 0;

}

# Output

std::bad_alloc

Allocation returned nullptr

12. new vs. malloc()

The main advantage of new over malloc() is that new does not just allocate memory, it constructs objects.

Foo* f1 = (Foo*)malloc( sizeof( Foo ) );

Foo* f2 = new Foo();

The difference is that the Foo object pointed to by f1 is not a proper object because its constructor was never called. The malloc() function only sets aside a piece of memory of a certain size. It does not know about or care about objects. In contrast, the call to new allocates the appropriate size of memory and also calls an appropriate constructor to construct the object. Similarly, the object’s destructor is not called from free(). With delete, the destructor is called and the object is properly cleaned up.

13. setting nullptr after freeing

It is recommended to set a pointer to nullptr after having freed its memory. That way, it prevents using accidentally a pointer to memory that has already been deallocated. For the record, calling delete on a nullptr pointer will not do anything.

14. memory allocation

Every process in Linux has a brk variable, which means ‘break’ and points to the bottom of the heap area. There is also a system call with the same name, which increases or decreases the size of the heap area by controlling brk. The following is the process of memory allocation by a function call such as malloc().

malloc()searches for a piece of free memory fragments and allocates a piece of appropriate size when it finds one.- If a piece of appropriate size cannot be found, the heap area is expanded through a system call such as

brk. Whenbrkexecution is finished, control returns to malloc, and the CPU switches from kernel mode to user mode. Nowmalloc()finds an appropriate piece of free memory and returns it.- The extended heap area is just virtual memory, and the memory returned by

malloc()is virtual memory. - In other words, the memory requested with

malloc()is kind of an empty promise, and at this point, no actual physical memory may have been allocated. - Actual physical memory is allocated at the moment the allocated memory is used.

- The extended heap area is just virtual memory, and the memory returned by

- Later, when the code reads or writes the newly allocated memory, the page fault interrupt occurs. At this time, the CPU switches back from user mode to kernel mode, and the operating system begins to allocate actual physical memory addresses. After the mapping between virtual memory and actual physical memory in the page table is established, the CPU switches back from kernel mode to user mode.

initialization

It cannot be assumed that dynamically allocated memory is always initialized to 0. There are two cases:

- If

malloc()keeps enough memory on its own, it looks for an address to return in this free memory. This memory may have already been used, and in that case, the memory may not be 0 because it may still have information about previous use. - If memory is expanded with a system call such as

brk, the operating system allocates physical memory through the page fault interrupt when the memory is actually used, so in this case, it may be initialized to 0.

pointer to memory already freed

What value is contained in the memory pointed to by a depends on the internal status of malloc().

void foo()

{

int* a = (int*)malloc( sizeof(int) );

// assign to *a ...

free( a );

int b = *a;

}

- If the piece of memory pointed to by

ahas not yet been reallocated withmalloc(), the value is the same as before. - If the piece of memory pointed to by

ahas already been reallocated withmalloc(), the value may have been overwritten.

15. reinterpret_cast is portable

This casting might seem as if it causes undefined behavior or not fully specified in the C++ Standard and, therefore, not guaranteed to be portable across all platforms. In fact, as of C++17, casting such related pointers between on another is explicitly guaranteed by the C++ Standard to work as intended on all platforms. According to cpp17, section 6.9.2, paragraph 4, p.82,

Two objects

aandbare pointer-interconvertible if (…) one is a standard-layout class object and the other is the first non-static data member of that object (…) If two objects are pointer-interconvertible, then they have the same address, and it is possible to obtain a pointer to one from a pointer to the other via areinterpret_cast(…)

C++20 introduces std::bit_cast, which is the only cast that is part of the Standard Library. The other casts are part of the C++ language itself. std::bit_cast resembles reinterpret_cast, but it creates a new object of a given target type and copies the bits from a source object to this new object. It effectively interprets the bits of the source object as if they are the bits of the target object. It requires that the size of the source and target objects are the same and that both are trivially copyable.

16. memory layout of C++ classes

C++ classes are a little different from C structures in terms of memory layout: inheritance and virtual functions. Data members of new derived classes are positioned after the data members of the base class, and padding may be included between each class due to memory alignment requirements. Multiple inheritance does some strange things, like including multiple copies of a single base class in the memory layout of a derived class.

If a class contains or inherits one or more virtual functions, then 4 additional bytes (or 8 bytes if the target hardware uses 64-bit addresses) are added to the class layout, typically at the very beginning of the class’ layout. These 4 or 8 bytes are called the virtual table pointer or vpointer, because they contain a pointer to a data structure known as the virtual function table or vtable.

17. signed division

Signed division must set the sign of the remainder. Rules are as follows.

- The absolute value of the quotient and remainder is the same as calculating both the dividend and divisor as positive numbers.

- If the signs of the dividend and divisor are the same, the sign of the quotient is set to be positive(+), and if they are different, it should be negative(-).

- The sign of the remainder is the same as the sign of the dividend.

// C++ Test Results.

7 / 2 = 3, 7 % 2 = 1

-7 / -2 = 3, -7 % -2 = -1

-7 / 2 = -3, -7 % 2 = -1

7 / -2 = -3, 7 % -2 = 1

Only for unsigned integers, a left shift instruction can replace an integer multiplication by a power of 2 and a right shift is the same as an integer division by a power of 2.

For signed integers, an arithmetic right shift that extends the sign bit instead of shifting in 0s is not a workaround. For example, a 2-bit arithmetic shift right of -5 (0x1011) produces -2 (0x1110) instead of -1, which means wrong.

18. auto& & auto*

Using auto to deduce the type of an expression removes reference and const qualifiers.

const std::string s("test");

const std::string& get() { return s; }

auto s1 = get();

const auto& s2 = get();

That is, in the above code, s1 is of type std::string, and thus a copy is made. So, explicit reference and const qualifier are needed to make it reference-to-const like s2.

When working with pointers, using auto* makes it more clear that pointers are involved, even though auto can deduce pointers. Additionally, the use of auto* does resolve a strange behavior when using auto, const, and pointers together.

int i = 123;

const auto p1 = &i;

const auto* p2 = &i;

Even though p1 seems like being of type const int*, the type is int* const, which means that it is a const pointer to a non-const integer. As expected, p2 is of type const int*.

19. literal pooling

A string literal is a value, not a variable. String literals are actually stored in a read-only part of memory. This allows the compiler to optimize memory usage by reusing references to equivalent string literals. That is, even if a program uses the string literal "hello" 500 times, the compiler is allowed to optimize memory by creating just one instance of hello in memory. This is called literal pooling.

Since string literals are in a read-only part of memory and because of the possibility of literal pooling, assigning them to variables can be risky. The C++ standard officially says that string literals are of type “array of const char“. However, for backward compatibility with older non-const-aware code, most compilers do not enforce programs to assign a string literal to a variable of type const char*. They allow assignment a string literal to a char* without const, and the program will work fine unless there is no attempt to change the string. Generally, the behavior of modifying string literals is undefined.

char* ptr = "hello";

ptr[1] = 'a'; // Undefined behavior!

It is also possible to use a string literal as an initial value for a character array. In this case, the compiler creates an array that is big enough to hold the string and copies the string to this array. The compiler does not put the literal in read-only memory and does not do any literal pooling.

char arr[] = "hello";

arr[1] = 'a'; // This contents can be modified.

20. std::string_view

It is better to use a std::string_view instead of const std::string& or const char* whenever a function requires a read-only string as one of its parameters. A std::string_view is a replacement for const std::string& but without the overhead. It never copies strings. It is usually passed by value because it is extremely cheap to copy. It just contains a pointer to, and the length of, a string.

However, functions returning a string should return a const std::string& or a std::string, but not a std::string_view. Returning a std::string_view would introduce the risk of invalidating the returned std::string_view if, for example, the string to which it refers needs to reallocate.

In addition, storing a const std::string& or a std::string_view as a data member of a class requires that the string to which it refers stays alive for the duration of the object’s lifetime. So, for this case, it is safer to store a std::string instead.

Lastly, do not use std::string_view to store a view of temporary strings. Once the temporary strings are destroyed, the std::string_view becomes a dangling pointer.

21. initialization order

ctor-initializers (constructor initializers) initialize data members in their declared order in the class definition, not their order in the ctor-initializer list.

class Bar

{

public:

Bar(double value) : m_value( value ) {}

private:

double m_value = 0.0;

};

class Foo

{

public:

//Foo(double value) : m_value( value ), m_bar( m_value ) {} // danger!

Foo(double value) : m_value( value ), m_bar( value ) {}

private:

Bar m_bar;

double m_value = 0.0;

};

The rule that objects are destroyed is in the reverse order of their construction. So, data member objects are destroyed in the reverse order of their declaration in the class. Similarly, objects on the stack are destroyed in the reverse order of their declaration and construction.

22. lvalue vs. rvalue

void foo(std::string&& str) {}

A named variable is an lvalue. So, inside the foo() above, the str rvalue reference parameter itself is an lvalue because it has a name. When forwarding this rvalue reference parameter to another function as an rvalue, std::move() is needed to cast the lvalue to an rvalue reference.

//void bar(std::string&& str) { foo( str ); } // compile error!

void bar(std::string&& str) { foo( std::move( str ) ); } // OK!

23. RVO (Return Value Optimization)

RVO is a form of copy elision and makes returning objects from functions very efficient. With copy elision, compilers can avoid any copying and moving of objects that are returned from functions. This results in so-called zero-copy pass-by-value semantics. Here are a few cautions.

do not disturb compilers with std::move()

Whether return object; is written or return std::move( object );, compilers treat it as an rvalue expression. However, by using std::move(), compilers cannot apply RVO anymore, as that works only for statements of the form return object;.

not for data members

RVO works only for local variables or function parameters. As such, returning data members of an object never triggers RVO.

ternary conditional operator

return condition ? object1 : object2;

This is not of the form return object;, so the compiler cannot apply RVO and uses a copy constructor. To use RVO, this code can be rewritten as follows.

if (condition) return object1;

return object2;

However, after testing this on the MSVC compiler and the GCC compiler with Compiler Explorer, this appears to be a result that only applies to the MSVC compiler.

24. one function embracing lvalue and rvalue arguments

It is better to prefer pass-by-value for parameters that a function inherently would copy, but only if the parameter is of a type that supports move semantics. This pass-by-value advice is suitable only for parameters that the function would copy anyway, and it only changes the copy timing. If an lvalue is passed in, it is copied exactly one time, just as with a reference-to-const parameter. And, if an rvalue is passed in, no copy is made, just as with an rvalue reference parameter.

However, consider this only if the move cost is not that large. According to observation, additional move construction may occur except when the rvalue is passed as a function parameter. This is because copy elision is applied to passing a temporary by value.

25. derived copy constructors

If a derived class does not specify its own copy constructor or operator=, the base class functionality continues to work. However, if the derived class does provide its own copy constructor or operator=, it needs to explicitly call the base class versions. If the base copy constructor is not explicitly called in the derived copy constructor, the default constructor will be used for the parent portion of the object.

26. flush()

Most output streams buffer, or accumulate, data instead of writing it out as soon as it comes in. This is usually done to improve performance. Certain stream destination, such as files, are much more performant if data is written in larger blocks, instead of, for example, character by character. The stream flushes, or writes out, the accumulated data, when one of the following conditions occurs.

- An

std::endlmanipulator is reached. - The stream goes out of scope and is destructed.

- The stream buffer is full.

- Explicit

flush()call. - Input is requested from a corresponding input stream. That is, when making use of

std::cinfor input,std::coutwill flush.

Not all output streams are buffered. The std::cerr stream does not buffer its output.

27. text mode vs. binary mode

In binary mode, the exact bytes asked the stream to write are written to the file. When reading, the bytes are returned exactly as they are in the file.

In text mode, there is some hidden conversion happening. Each time \n appears in a file, one line is read or written. However, how the end of a line (EOL) is encoded in a file depends on the operating system. For example, on Windows, a line ends with \r\n instead of with a single \n character. Therefore, when a file is opened in text mode and it writes a line ending with \n, the underlying implementation automatically converts the \n to \r\n before writing it to the file. Similarly, when reading a line from the file, the \r\n that is read from the file is automatically converted back to \n before being returned.

28. errors in constructors

What if a constructor fails to construct the object properly? If an exception leaves a constructor, the destructor for that object will never be called. But, if a derived class constructor throws an exception, C++ will execute the destructor of the fully constructed base class. C++ guarantees that it will run the destructor for all fully constructed subobjects. Therefore, any constructor that completes without an exception will cause the corresponding destructor to be run.

29. conversions for boolean expressions

Sometimes it is useful to be able to use objects in Boolean expressions. For example, the following conditional statements are used.

if (p != nullptr) { /* ... */ }

if (p) { /* ... */ }

if (!p) { /* ... */ }

The usual pointer type for the conversion operator is void*.

operator void*() const { return ... }

With operator bool(), the comparison with nullptr results in a compilation error. This is because nullptr has its own type called nullptr_t, which is not automatically converted to the integer 0 (false). The compiler cannot find an operator!=. Even if operator!= is implemented, the comparison like if (p != NULL) stops working, because the compiler no longer knows which operator!= to use. Unfortunately, even then, adding a conversion operator to bool presents some other unanticipated consequences. So, many programmers prefer operator void*() instead of operator bool().

30. std::vector<bool>

The C++ standard requires a partial specialization of std::vector for bools, with the intention that it optimizes space allocation by packing the Boolean values. But, C++ does not have a native type that stores exactly one bit. Some compilers represent a Boolean value with a type the same size as a char, and others use an int. The std::vector<bool> specialization is supposed to store the array of bools in single bits, thus saving space.

However, note that std::vector<bool> returns a reference object, which is a proxy for the real bool, when calling operator[], at(), or a similar method. So, its address cannot be taken to obtain the pointer to the actual elements in the container.

Even worse, accessing and modifying elements in a std::vector<bool> is much slower than, for example, in a std::vector<int>. Many C++ experts recommend avoiding std::vector<bool> in favor of the std::bitset. Even though the benefit of std::vector<bool> is that it can change size dynamically, it can still be replaced by something like std::vector<std::int_fast8_t> or std::vector<unsigned char>. The std::int_fast8_t is a signed integer type for which the compiler has to use the fastest integer type it has that is at least 8 bits.

31. std::span

std::span, introduced in C++20, allows to write a single function that works with std::vectors, std::arrays, and C-style arrays. It could look like a form of std::span<int>. Note that, just as with std::string_view, a std::span is cheap to copy because it basically just contains a pointer to the first element in a sequence and a number of elements. A std::span never copies data. As such, it is usually passed by value.

Unlike std::string_view which provides a read-only view of a std::string, a std::span can provide read/write access to the underlying elements. Since it never copies data, modifying its element actually modifies the element in the underlying sequence. If this is not desired, a std::span of const elements can be created like std::span<const int>. So, consider accepting a std::span<const T> when writing a function accepting a const std::vector<T>&.

32. try_emplace() on std::map

Prefer try_emplace(), and consider insert_or_assign() if overwrite is needed. A few methods to add elements are as follows.

try_emplace()— does nothing if the key already exists.emplace()— no overwrite, but the element may be constructed even if there already is an element with the key.insert_or_assign()— overwrite unlikeinsert().operator[]— overwrite, and it always constructs a new value object even if it does not need to use it. requires a default constructor. less efficient thaninsert().

33. capturing lambda

Before C++20, [=] would implicitly capture the this pointer. In C++20, this has been deprecated, and it requires explicitly capturing this.

Global variables are always captured by reference, even if asked to capture by value. Additionally, capturing a global variable explicitly is not allowed and results in a compilation error. So, global variables are never recommended anyway.

int global = 42;

int main()

{

//auto lambda = [global]{ global = 2; }; // compile error!

auto lambda = [=]{ global = 2; };

lambda(); // global value modified

}

34. std::erase_if()

The following code has been often used to remove elements in std::vector. However, this solution is inefficient as it will cause a lot of memory operations to keep the std::vector contiguous in memory, resulting in a complexity.

void removeElements(std::vector<std::string>& v)

{

for (auto it = v.begin(); it != v.end();) {

if (condition_to_remove) it = v.erase( it );

else ++it;

}

}

Starting with C++20, std::erase_if() is the preferred way to remove elements which has a complexity.

void removeElements(std::vector<std::string>& v)

{

std::erase_if( v, [](const std::string& s){ return condition_to_remove; } );

}

35. std::random_device

The std::random_device engine is not a software-based generator. It is a special engine that requires a piece of hardware attached to a computer that generates truly non-deterministic random numbers, for example, by using the laws of physics. A classic mechanism measures the decay of a radioactive isotope by counting alpha-particles-per-time-interval, but there are many other kinds of physics-based random-number generators, including measuring the noise of reverse-biased diodes eliminating the concerns about radioactive sources in the computer.

According to the specification for std::random_device, if no such device is attached to the computer, the library is free to use one of the software algorithms. The choice of algorithm is up to the library designer. The entropy() method of the std::random_device engine returns 0.0 if it is using a software-based pseudorandom number generator and returns a non-zero value if it is using a hardware device. The non-zero value is an estimate of the entropy of the hardware device.

A std::random_device is usually slower than a pseudorandom number engine. Therefore, if there is a need to generate a lot of random numbers, it is recommended to use a pseudorandom number engine and to use a random_device to generate a seed for the pseudorandom number engine. The std::mersenne_twister_engine generates the highest quality of random numbers. The period of a Mersenne twister is a so-called Mersenne prime. For example, the predefined Mersenne twister std::mt19937 has a period of , while the state contains 625 integers or 2.5 KB. It is one of the fastest engines.

36. thread local storage

The C++ standard supports the concept of thread local storage. With a keyword called thread_local, any variable can be marked as thread local, which means that each thread will have its own unique copy of the variable, and it will last for the entire duration of the thread. For each thread, the variable is initialized exactly once.

Note that if the thread_local variable is declared in the scope of a function, its behavior is as if it were declared static, except that every thread has its own unique copy and is initialized exactly once per thread, no matter how many times that function is called in that thread.

37. spurious wakeup

Threads waiting on a condition variable can wake up when another thread calls std::condition_variable::notify_one() or std::condition_variable::notify_all(), with a relative timeout, or when the system time reaches a certain time. However, they can also wake up spuriously. This means that a thread can wake up even if no other thread has called any notify method and no timeouts have been reached yet. This can be resolved by using std::condition_variable::wait() accepting a predicate.

38. std::async()

std::async() accepts a function to be executed and returns a std::future containing the result. The way how std::async runs depends on factors such as the number of CPU cores and the amount of concurrency already taking place. Although the runtime automatically chooses the method, the runtime’s behavior can be specified by a policy argument.

std::launch::async— forces the runtime to execute a function asynchronously on a difference thread.std::launch::deferred— forces the runtime to execute a function synchronously on the calling thread whenstd::future<T>::get()is called.std::launch::async | std::launch::deferred— lets the runtime choose (default behavior).

One caveat is that a std::future returned by a call to std::async() blocks in its destructor until the result is available. For example, the following line calls foo().

std::async( foo );

The returned std::future is not captured, so it is a temporary std::future. As such, its destructor is called at the end of this statement, and this destructor will block until the result is available. That is, this line is just synchronously calling foo().

39. link time optimization

Inlining requests are only a recommendation to the compiler, which is allowed to refuse them. On the other hand, some compilers inline appropriate functions and methods during their optimization steps, even if those functions are not marked with the inline keyword and even if those functions are implemented in a source file. In Visual C++, for example, this feature is called link-time code generation (LTCG) and supports cross-module inlining. The GCC compiler calls it link time optimization (LTO).

40. name mangling

To implement function overloading, the complex C++ namespace is flattened.

void foo(double);

void foo(int);

For example, for the overloaded functions as above, the linker would not know which one must be called. Therefore, all C++ compilers perform an operation that is referred to as name mangling and the result might look as follows.

foo_double

foo_int

To avoid conflicts with other names defined, the generated names usually have some characters that are legal to the linker but not legal in C++ source code.

?foo@@YAXN@Z

?foo@@YAXH@Z

This encoding is complex and often vendor-specific. The C++ standard does not specify how function overloading should be implemented on a given platform, so there is no standard for name mangling algorithms.

41. extern "C"

In C, function overloading is not supported. So, names generated by the C compiler are quite simple, for example, _foo. However, the C++ compiler still generates a request to link to a mangled name, even if a program has only one instance of the foo name. As a result, when linking with the C library, it cannot find the desired mangled name, and the linker complains. Therefore, it is necessary to tell the C++ compiler to not mangle that name. This is done by using the extern "C". This extern keyword informs the compiler that the linked-in code was compiled in C.

References

[1] Peter van der Linden. 1994. Expert C programming: deep C secrets. Prentice-Hall, Inc., USA.

[2] Marc Gregoire. 2021. Professional C++, Fifth Edition. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

[3] J. Gregory. Game Engine Architecture, Third Edition. CRC Press

[4] J. Lakos. Large-Scale C++ Volume I: Process and Architecture. Addison-Wesley Professional

[5] 전상현. 2018. 크로스 플랫폼 핵심 모듈 설계의 기술, 로드북

[6] 루 샤오펑. 2024. 컴퓨터 밑바닥의 비밀, 길벗